Origin of South Korea's anti-Rising Sun flag campaigns

MURAWAKI Yugo

Created: November 8, 2015.

Last Update: December 30, 2018.

tl;dr: South Korea's anti-Rising Sun flag campaigns are racist and historically unfounded.

Introduction

Thanks to the web that keeps archiving human activities, we can retrospectively obtain a precise answer to the question, "when and how did it happen?" In this article, I take a data-driven approach to revealing the origin of South Korea's anti-Rising Sun flag campaigns.

Both within and outside Japan, the rising-sun motif is closely associated with Japan, the land of the rising sun. Arguably, the most famous use of the motif is of military. The Imperial Japanese Army/Navy used several variants of the Rising Sun flag. Today these are reused by the Japan Self-Defense Forces with minor modifications. This means that the Rising Sun flag has caused no problem in Japan's international relations. In fact, when South Korea hosted international fleet reviews in 1998 and 2008, Japanese naval ships flew the rising sun flags with no trouble [1]. What is more, the U.S. army in Japan happily adopted the rising-sun motif for its emblems. It is also important to note that the use of the flag is not limited to military affairs. We can found the motif in the logo of Asahi Shimbun (lit. morning sun newspaper), Asahi Gold beer by Asahi Breweries, and fishermen's tairyō-bata (lit. big catch flag), just to name a few. It is not an exaggeration to say that the rising-sun motif forms an integral part of Japanese culture. No one who is supposed to promote cultural diversity can tolerate hate speech toward one nation's cultural symbol.

Recently, however, South Koreans have gotten mad at the use of the rising-sun motif. Here is an incomplete list of materials they have targeted at:

- April 2012: a soccer team uniform of the University of Missouri.[2]

- August 2012: uniforms for Japanese gymnasts at the London Olympics.[3]

- March 2013: a New Year poster by Kyary Pamyu Pamyu, a Japanese fashion model and singer.[4]

- March 2013: a gi worn by Canadian martial artist Georges St-Pierre.[5]

- April 2013: a music video by British rockers Muse.[6]

- April 2014: a promo poster for American movie Godzilla (2014).[7]

- April 2015: KamikazeM, a bike shirt by German company Maloja.[8]

- May 2015: a T-shirt worn by American actress Kristen Stewart.[9]

- May 2015: a backdrop displayed during the performance of British singer-songwriter Mika.[10]

- July 2015: an online game named World of Warships.[11]

- October 2015: a logo used by a sushi restaurant at the University of Missouri.[12]

- October 2015: sneakers by Asics.[13]

- November 2015: the flags displayed at Brigham Young University.[14]

- August 2016: the flag flown in front of Kauai Museum, Hawai'i.[15]

- October 2016: shoes worn by a fictional character in a video game Persona 5.[16]

In these campaigns, South Koreans try to associate the Rising Sun flag to World War II. They even attempt to equate it with Nazi Germany's Hakenkreuz. Also, if you read Korean, you would notice that a weird phrase "war criminal flag" (전범기) routinely appears in these campaigns. It looks as if it has been used for decades. If their claim is truly historically founded, their anti-Rising Sun flag campaigns must also have deep roots in history.

Using web data, I will show that these campaigns started just a few years ago and have a racist connotation. The key findings are as follows:

- South Korea's anti-Rising Sun flag campaigns became active in 2013.

- They were triggered by two Japan–South Korea football matches in January 2011 and August 2012. In both events, South Korea's accusation against the Rising Sun flag was aimed at deflecting blames from its own wrongdoings (a racist slur against Japanese people for the former and an on-field display of a politically charged sign for the latter).

- The new phrase "war criminal flag" (전범기) was coined in August 2012.

Google Trends

The South Korean variety of Korean has as least three names for the Rising Sun flag (McCune–Reischauer romanization for Korean):

- ugilsŭngch'ŏn'gi (욱일승천기). The most common name.

- ugilgi (욱일기). A shorter form.

- chŏnbŏmgi (전범기), lit. war criminal flag.

Since the last, emotionally-charged phrase is essentially linked to the anti-Rising Sun flag campaigns, I begin by investigating it.

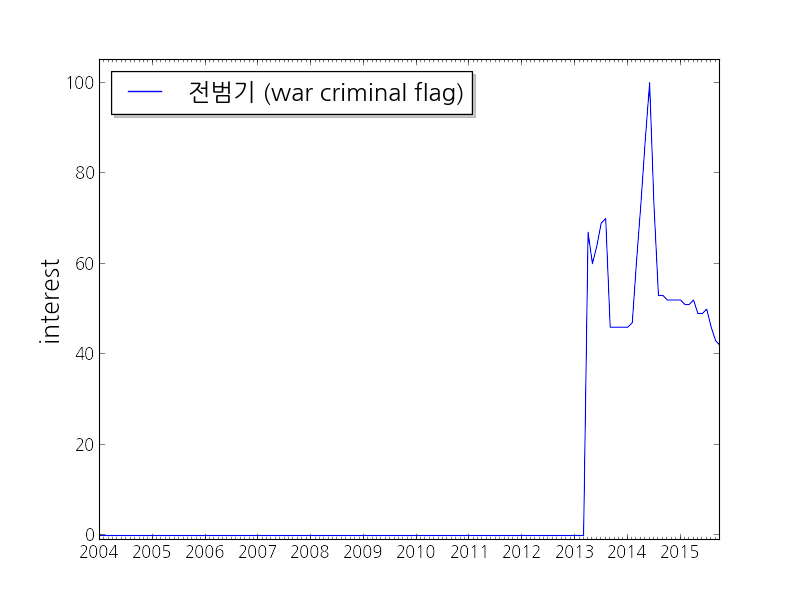

As of November 2015, Google Trends returns the following time-series chart for "war criminal flag" (전범기):

You can see that the first non-zero value is of April 2013. Before that, the phrase in question had no enough search volume. Thus we can conclude that South Korea's anti-Rising Sun flag campaigns became visible as late as 2013.

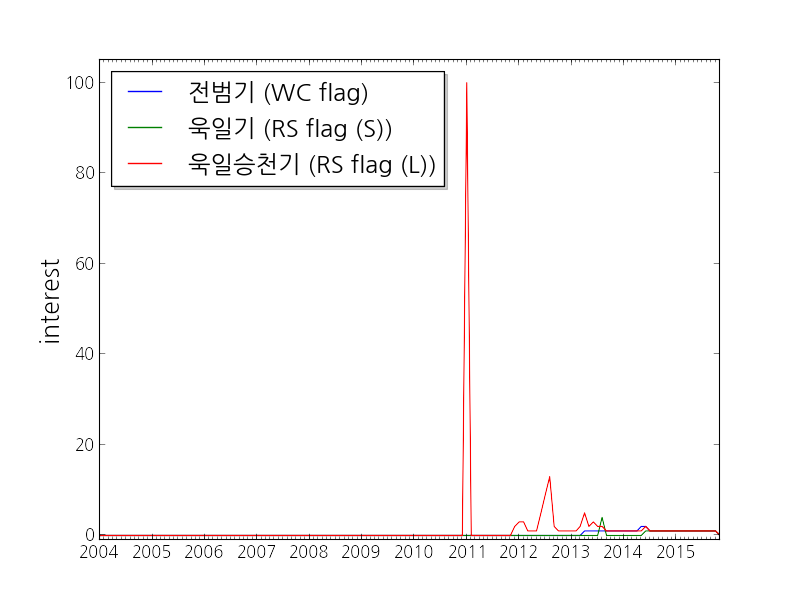

Next, it is compared with the remaining two phrases.

The longer name (욱일승천기) is by far the most common. There were two major bursts, firstly in January 2011 and secondly in August 2012. Later in this article, I will explain what caused these bursts. What is important at this point is that before 2011, all these phrases failed to gain non-zero values. It was in 2011 that South Koreans suddenly got interested in the flag. Considering the fact that about 70 years have passed since World War II, you may naturally wonder why their anti-Rising Sun flag campaigns do not have deep roots in history.

Naver Trend

My findings above are supported by another source: Naver Trend. Naver Trend is a South Korean equivalent of Google Trends. Since Naver has almost 80% of the South Korean search market [17], it might be able to capture relatively minor trends that Google ignores.

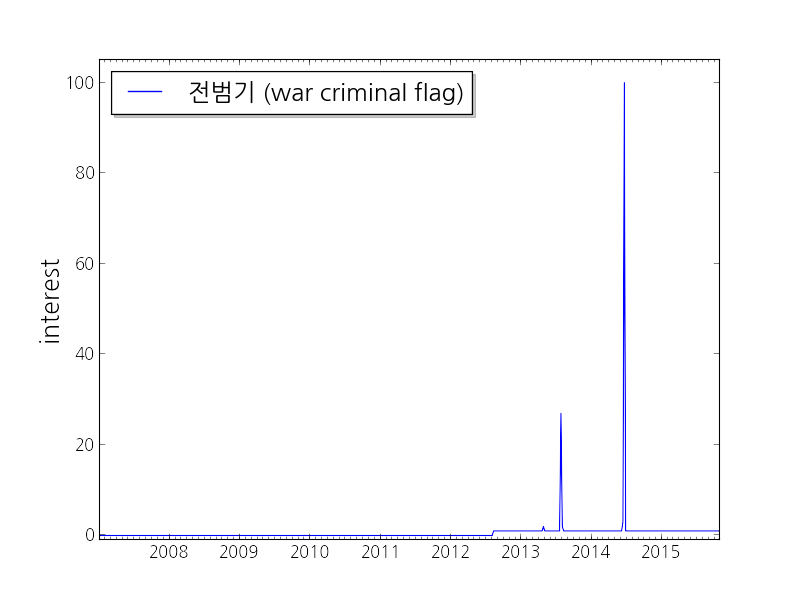

The first non-zero value for "war criminal flag" (전범기) is of the week of August 6 to 12, 2012. Although it is 8 months earlier than that of Google Trends, it coincided with the second burst of the longer name (욱일승천기) in Google Trends.

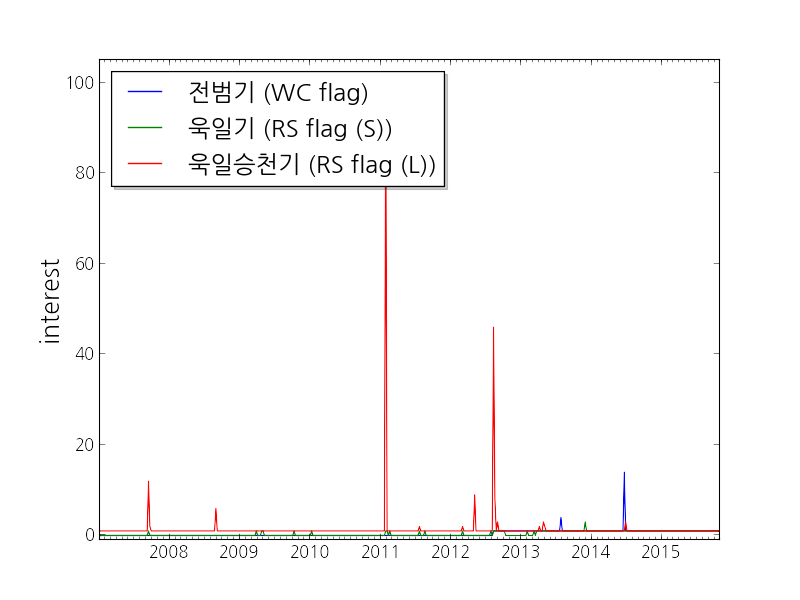

Combining the three phrases, we can observe the same two bursts as those of Google Trends: the first, larger one is of the week of January 24 to 30, 2011, and the second one is from August 6 to 19, 2012.

Throughout the period examined, the longer name (욱일승천기) managed to keep non-zero values. However, the scores were overwhelmingly dominated by ones, and only two small spikes occurred before 2011. The shorter name (욱일기) might be a better indicator of interest in the flag: the continued interest in the flag (indicated by uninterrupted non-zeroes) only started in March 2013. We have no need to modify the conclusion that South Korea's anti-Rising Sun flag campaigns became active in 2013.

News

A useful property of Naver Trend is that it links each burst to newspaper articles. Now let us see what triggered the bursts of January 2011 and of August 2012.

For the newer burst, newspaper articles point to a football match at the London Olympics on August 10, 2012 [18][19]. In these articles, South Korean media criticized uniforms for Japanese gymnasts that featured the rising sun. Why was gymnastics related to football? It sounds strange to us, but a closer look reveals that what they did was a logical fallacy known as tu quoque or whataboutism. By making an accusation against Japan, they attempted to deflect criticism over their own wrongdoing: at the end of the football match, a South Korean player named Park Jong-woo displayed the sign with a slogan of justification for South Korea's occupation of disputed islets. That was a clear violation of the statues of both the IOC and FIFA that prohibit political statements by athletes and players. It was no wonder that he was banned from the subsequent medal ceremony. South Korea's reaction was uncontrollable fury. They were unable to resist the temptation to run down Japan, and all they found was the rising-sun motif.

As for the older burst, it is, again, linked to a football match on January 25, 2011 [20][21][22], and once again, the Rising Sun flag was used as a whataboutism excuse (are South Koreans big fans of whataboutism?). At that match, South Korean footballer Ki Sung-yueng celebrated his goal by scratching his face in a monkey-like fashion, a racist slur at Japanese people. The next day, he posted a Twitter message claiming that he had been annoyed at having seen a Rising Sun flag in the stadium. While he succeeded in drawing sympathy within South Korea, he appeared to have been aware of how lame his excuse was, as he did not repeat it on a formal basis. It is worth noting that he flip-flopped his remark. He later claimed that the celebration was a reference to alleged racist taunting by St Johnstone fans during a Scottish Premier League game.

In our search for the origin of South Korea's anti-Rising Sun flag campaigns, Ki's racist slur of 2011 was undoubtedly a decisive point in time. In response to the flame, South Korean media openly advocated tactics of defaming the Rising Sun flag by equating it with Nazi Germany's Hakenkreuz [23]. To my knowledge, this is the first instance of the South Korean narrative we hear these days.

Lastly, I searched the news archive of JoongAng Ilbo for "war criminal flag" (전범기) [24]. Unfortunately, it returned many more results than it should have done. Its search engine employed simple string matching, and the phrase in question was a substring of "war criminal company" (전범기업). If my manual filtering is correct, its first attested use is of August 16, 2012 [25]. In that column, the author Kim Ch'igim urged readers to call the Rising Sun flag a "war criminal flag" (전범기). It is not clear whether he coined the phrase by himself, as it was detected by Naver Trend a week earlier. Anyway, it is safe to conclude that the new phrase "war criminal flag" (전범기) was coined in August 2012.

Conclusion

Today, once your use of the rising-sun motif gets noticed by South Koreans, you will be bothered by an endless stream of protests from them. Their obsession with what they believe is "correct" history is well known. In fact, their restless focus on historical disputes leads to what is known as "Korea fatigue" in U.S. and Japanese diplomacy [26]. In this article, I presented one instance for which their claim is not historically founded at all. My time-series analysis found that their anti-Rising Sun flag campaigns can only be traced back to 2011 when they abused the flag to deflect criticism over a South Korean footballer's racist slur against Japanese people.

To be precise, I do not claim that South Koreans had never expressed their hatred toward the Rising Sun flag before 2011. The important point is that what we see today is clearly different from what we saw in the past. South Korean demonstrators used to burn the Hinomaru (national flag of Japan), slash an effigy of former Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi, cut down cherry blossom trees (another important symbol for the Japanese culture), and destroy historic buildings Japan constructed in the peninsula. In other words, they did not single out the Rising Sun flag. Thus it is reasonable to ask what makes this qualitative difference. In this article, I showed that the answer lies in the fact that the current campaigns postdate the racism row of 2011.

Although the phrase "painful memories" is a cliché you are likely to hear from South Koreans, their anti-Rising Sun flag campaigns ironically symbolize a severe loss of collective memory. If one knows what the rising sun motif means to the Japanese nation, she can immediately recognize that she would cross the red line if she call for an international ban on the rising sun motif. The older generations, who had firsthand knowledge about Japan, could do that, but they failed to pass down the remembrance to younger generations. That is why anti-Rising Sun flag protesters are ignorant about the cultural significance of the motif.

For their deep connection to football, I came up with an analogy between anti-Rising Sun flag protesters and hooligans. The former is certainly less violent but they are equally unproductive. They both waste a tremendous amount of energy. Maybe one difference is that the former has demonstrated creativity by reshaping their collective memory in an astonishingly short period of time. If they made efforts in the right direction, the world would be a better place. The first step toward the solution is to let them learn that what they are doing is fruitless.